GENESIS OF THE INDIAN POPULAR CINEMAThe eighties: When Screen Meanies Grow Meaner… - part one

"The blood-dimmed tide is loosed and everywhere / The ceremony of innocence is drowned." (W.B. Yeats) "Personal relations are the important thing for ever and ever, and not this outer life of telegrams and anger… Only connect the prose and the passion… Only connect and the beast and the monk, robbed of the isolation that is life to either, will die." (E.M. Forster, Howards End) "Contrary to common belief the most significant development in 80s’ pop has not been the rise of dance music but the installation of a pop aristocracy. The pop aristocracy cherish the romantic escapist tradition." (Stuart Cosgrove, New Statesman and Society)

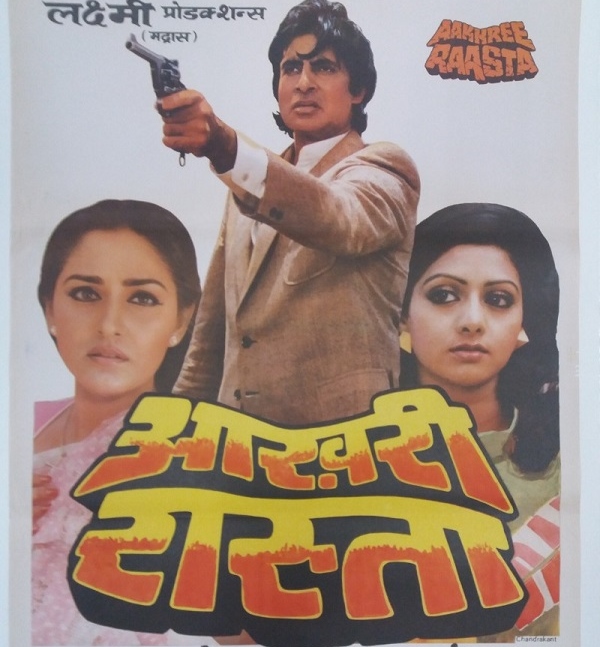

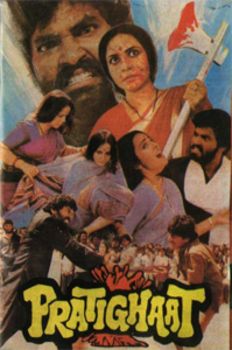

I shall revert to these points later in the article. But first the political-social-institutional backdrop to the cinema of the 80s. The relationship of the two is not mechanistic. But over a decade a significant causal relationship emerges. The 80s are probably the most turbulent decade in India's post-independence history. At the beginning of the 80s there was the 'Restoration' of Mrs. Indira Gandhi. The euphoria ebbed as the intractability of the country's problems - Punjab, Assam, Gorkhaland, Sri Lanka, economic stagnation, increasing rural misery, a weak and corrupt administration - became increasingly obvious. There was a second round of euphoria in the mid-80s with new people in power. Economic liberalism did not lead to percolation of goodies down to the poorest as had been hoped but to concentration of power in the hands of the rich. On the social side,it led to the rise of a Yuppie class with its concomitant of pseudocomputer culture and avid consumerism. On the cultural side it led to what may be called the cretinization of the urban intelligentsia - specially of the young. Writing, criticism, film, theatre became little more than monitoring and publicising 'new waves'. Take up any quality paper today. A cinematic or theatrical trend - or even individual works - are taken up, superficially 'discussed' (which means praised) and thrown away like disposable junk even before they come on view. This has had a deleterious effect on cinema. Films - even middle cinema films - are now managerially made - with a view to what the market 'will take'. No wonder the products are so depressingly similar. There's another important aspect. Recently a 'new' (but good) filmmaker asked me: "Are you aware of the changes in the audience?" I told him: "I have been sitting with the audience since 1936". A detailed examination of audience change over 50 years is beyond the scope of this article. But I can say this of the 70s and 80s audience in the theatres. The middle classes have retreated to the safety of T.V. and V.C.R. lounges. The lower middle classes too watch borrowed V.C.Rs. in their modest living rooms. The theatres are left to the lumpen. When I protested on being pushed at a showing of Aakhri Raasta, I was told: "for a picture like this one must push". The taking over of commercial theatres by rootless proles is a fact of life. Films like Hukumat and Aag Hi Aag simultaneously appeal to and degrade their audiences. You can palpably feel the degradation taking place as you watch such films in our crowded, polluted, bug-ridden and rat-infested theatres. At such moments you wish you had the stamina to laugh at the memory of 'good cinema' seminars you attended. And now to the financial state of the film industry. It's – in one word - a mess. l will spare you the details. They are all there in two well-written articles - Hindi Cinema 1987 by Sanjit Narwekar (Indian Cinema 1987, pub: Directorate of Film Festivals of India) and Good Times, Bad Times by M. Rehman (India Today, May 11 1988). Surplus of black money, paucity of theatres, high star prices, a crazy Gadarene rush into the sea of disaster - it's all there. But my concern is not with the fate of the film industry. It's to do with the nature of the industry and its effect on the product. The Indian film industry ever since the forties has exhibited two features. One, it is highly speculative and unorganised. Second, every one in the industry (and today this includes the new cinema people) is driven either by avarice or a clutch for security. This applies to producers, directors, actors and technicians.1988 is not so very different from 1950. The trash of 1950 is glamorised by nostalgia whereas the 1988 product's mediocrityl nastiness is too fresh to be acceptable. This is a large statement. It's meant to be. Hindi Cinema has been flawed these last four decades by a basic contradiction. The medium had the potential to give India not merely a new aesthetic but a new ethos. But it was rooted in a financial and social culture that was basically and irredeemably corrupt and corrupting. A few swallows - Guru Dutt, Raj Kapoor among others - do not convert this wintry darkness into bright summer. And even the swallows were overwhelmed by the enveloping miasma. The eighties are only the culmination of a long process of debasement. The history of Hindi popular cinema in the 80s is the history primarily of the interaction between the political and social turbulence, the economic decay of cinema industry and the need of the filmmakers to give the audiences welltried themes which will reassure them and to vary such themes by the right touch of innovation to ensure a hit. In the 1980s the politico-economic situation has become desperate. So has the cinema industry economic situation. Hence the abysmal quality of Hukumat, Pratighat, Nagina - films of the last two years which can be regarded as box-office hits. Looking back from bleak 1988, the first year of the decade, 1980-81, looks positively an annus mirabilis, a year of wonders. There is a vigour, a drive, a charm in the films of this year. It would not be too fanciful to relate this to the political and social euphoria of the Restoration. The relative innovation of these films began to run down in later years reaching a nadir in the present year. 1980-81 also set many trends in themes, narrative structures and cinematic and acting styles. At the risk of being schematic, let me set down some of the important films in terms of categories - arbitrary and subjective, but useful. The first category is of the vendetta - vigilante violence and sex exploitative 'action film'. This was to be the leading genre of the decade. It had germinated in the seventies but it came to full bloom in the 80s. The trend was set by Qurbani, Naseeb and Kranti. It's astonishing how little change has taken place in the 80s in the patterns set by these films eight years ago.

Qurbani had certain elements which made it a hit. It speeded up the action in a very American fashion. It gave you trendy pop music and songs - one of the first to serve up pop in desi [deshī = "del paese", "locale", "indigeno"] lingo. It gave you male bonding of a special kind - the great brotherly macho love which turns into hate (Firoze Khan and Vinod Khanna). The other side of this coin is unbridled violence. Qurbani was the most violent Hindi film (recall not merely the fights but the smashing of the Mercedes in the parking lot) upto that time. It was violence of a specific kind. Frankly, it was neo-colonial - not in the orthodox but in a subtle sense. The furious cutting pace, the trendy wear of the men and the girl (Zeenat), the tough dialogue, the skilful beating up and mauling are all out of American action films or cops-and-robbers T.V. serials. This two-faced coin of male bonding and zippy violence was continued through the eighties in films too many and too unmemorable to name. I would call this cinematic development of the 80s a perfect instance of Hindi Cinema's total cultural dependence - indeed slavery - to the West.The crash helmets and the leather jacket are today as typical of the trashy Hollywood film, as of our best action film. A fall out of this macho culture was the total elimination of women as 'heroines'. Zeenat in Qurbani is the attractive marionette - a glossy 'liberated' nightclub singer who is no more than a humble adornment of the film's rampant machismo. Gone are the days of Nargis, Nutan and Meena Kumari when women existed in their own right as recognisable, idiosyncratic, desirable individuals. Qurbani is a kind of a bench-mark in the downgrading of women in our cinema. Today Amrita Singh, Neelam, Madhuri are all mediocre imitations of the Zeenat persona. What about the great Sridevi? I do not think she breaks the mould. In the recent Sherni, one of her finest panache performances, she is a man in a woman's form, not a woman in her own right. Another original contribution of Qurbani (a good one) was its element of comedy. This was a far cry from the comedy of Kishore Kumar - the native, nuanced referenced craziness. Amjad Khan brought the contemporary Euro-American looniness into Indian cinema. Not all foreign influences are bad. The anarchy of the 60s and 70s western comedy was needed to make a dent in our much-vaunted '5000-year old parampara [paramparā = "tradizione"]. Inspector Amjad Khan, fast talker, great mimic, aggro-farceur did just that. This modern comic trend caught on - but fizzled out. The splendidly crazy, satirical caricatures of Kundan Shah's Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro died in the T.V. wastes of Yeh Jo Hai Zindagi. When you watch a specific phenomenon like this, you reluctantly concede Nirad C. Chowdhary's Continent of Circe thesis - in our culture gold soon turns to brass - and worse. The same applies to Sai Paranjpye's progression from the superb Chashme Buddoor to Katha to the insipid T.V. serials. Iqbal Masud Film citati nell'articolo (anno, regista, lingua): A cura di |