GENESIS OF THE INDIAN POPULAR CINEMAThe Early Period - part one

"Bombay Film is a transformation of the narrative structures... Mahabharata and Ramayana... What we have in fact is not one 'super' narrative but also a predominant genre whose rules are to be discovered in films from Phalke's Raja Harishchandra (1913) to the latest blockbuster from Bombay." (Vijay Mishra, Screen, London 1985). "Hindi films are contemporary myths which, through the vehicle of fantasy and the process of identification, temporarily heal for their audiences the principal stresses arising out of Indian family relationships." (Sudhir Kakar, "Indian Popular Cinema, Myth, Meaning and Metaphor", India International Centre Quarterly, 1981). "The vast popularity of Indian cinema has deep roots in the continuing traditional character of Indian culture. It is, therefore, pointless for the elite to blame the cinema industry for producing subzero quality films." (Akhileshwar Jha, "Sexual Designs in Indian Culture", 1979). "Most Indian critics and reviewers of any standing will not give much quarter to the 'commercial' cinema. Its greatest days may indeed have passed but no commercial system that could accommodate filmmakers like Phalke, V. Shantaram, S.S. Vasan, Mehboob Khan, Guru Dutt and Bimal Roy could possibly be so debased as to be completely worthless now." (Derek Malcolm, Sight and Sound, 1986). Something must indeed be up if professors of English literature, a psychiatrist and a renowned English film critic evince keen interest in the roots of Hindi popular cinema, sound a valedictory note over its threatened demise and abuse "elitist" critics. Popular cinema constituents - directors, technicians, writers, artists - feel beleagured both financially and critically. Television, video piracy, taxes, "ivory tower" critics, all seem to have ganged up. At the same time a host of cultural anthropologists, popular culture-vultures or just rootless natives who discover their identity in masala ["spezie", film popolare, oggi Bollywood] films, have sprung up to define, idolise and reverently analyse popular cinema. This enthusiasm seems odd to someone (like this writer) who has moved, lived and had his being in the Hindi popular cinema during the last half century. But then, as the philosopher said: "Minerva's owl takes flight in the gathering dusk." The undertakers are anxious to be on the scene before the funeral rites. This concern is to be taken note of but at the same time one must point out the limitations of the approach in the passages quoted above. First, the authors have adopted a Procrustean-bed approach to popular cinema. "Popular cinema" is confined to certain patterns - possibly mythic (ancient epics), possibly box-office success (appeal to millions). The "other" films are cast into outer darkness. Second. no detailed examination of individual films is attempted. Third, the interplay between the myths, the modern mythmakers and those who receive the myths is not explored. Fourth, (this is a minor point), the work of 'elitist' critics is never examined in detail (or is examined in a selective fashion). In this article and those which follow, I do not propose to set right all these limitations. My purpose is a narrow one: To discuss certain recurrent themes and their variations in popular cinema. The approach generally follows that of Umberto Eco in his article "Innovation and Repetition" (Daedalus, Fall 1985): "The principal features of mass media products are repetition, reiteration, obedience to a pre-destined scheme, and redundancy (as opposed to information)". This is as true of Manmohan Desai, as of Steven Speilberg's Raiders of the Lost Ark and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Both Hindi popular cinema and modern T.V. serials (West or East) work on a fixed situation and a restricted number of fixed pivotal characters around whom the secondary and changing ones revolve. As true of Raja Harishchandra as of Mard. We believe we are enjoying the novelty of a Hindi film while in fact one is enjoying it because of a narrative scheme that remains constant. And yet the Hindi popular film must make those variations within "the horizon of expectations" or perish. There is a subtle difference between Coolie and Allah Rakha (the fact that one succeeded at the box office and the other did not is immaterial) which the cognoscenti recognise and relish. Themes and variations are equally important. Also important is the interplay between the themes, the variations and the socio-historical context.

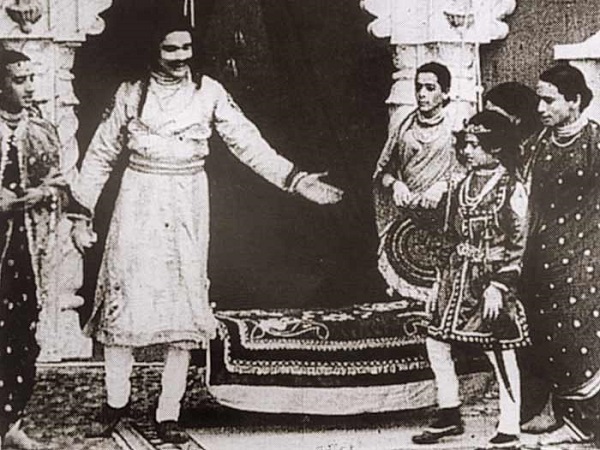

The middle two reels of Raja Harishchandra are still missing at the Film Archives in Pune. What we have are only the first and the last reels. But the original film, which was tremendously popular, greatly influenced the later re-workings of the same story. Certain elements of the story surfaced in much later "secular" films (as I shall show later). In the present condition of the original film let us turn to an established version of the Harishchandra myth. This will clarify its later reverberations and variations in the popular cinema. One of the established versions is the drama of Satyaharishchandrayamu by Belijepalli Lakshmikantam (1920) which is regularly performed in the Vishakapatnam district by farmers and carpenter castes. The story has been carefully analysed by Professor Bruce Elliott Tapper (Culture and Morality, 1981). This version differs from Phalke's version to some extent but the differences are generally marginal. The narration begins with a quarrel between the sages Vasishta and Viswamitra. Vasishta places satyam (truth) above fame, sacrifices to Gods, vows and worship. Viswamitra disagrees. Vasishta says, Harishchandra of Ayodhyapuram will never tell a lie. Viswamitra says he can create circumstances which can cause even this King to tell a lie or break a promise. Both the film and the play centre around Viswamitra's attempts to break the King's resolve to live truthfully. The manner in which the King's obligation to Viswamitra arises, shows interesting variations between the film and the play. In the film it is Harishchandra's meritorious act (freeing some spirits from Viswamitra's spell) that causes Viswamitra's ire and makes him punish the King with the demand of his kingdom and further levies, reducing the King to becoming a labourer. In the play it is the King's refusal to marry two untouchable girls at Viswamitra's bidding, that causes the trouble. In the play the King says he would rather abdicate his kingdom than violate his caste laws (Kulaprathanadharmamu). Challenged by the sage, the King gives up his kingdom. The difference between the two versions is significant. Phalke had been "westernised" to some extent. After all he had turned towards cinema after seeing an American film about Christ. The idea of caste preservation must have been abhorrent to him. But the tradition of the people was caste structured. To a certain extent this tradition was sanitised in popular cinema. Later filmic developments confirm this tendency. The death of Karna in the Mahabharata is richly ambivalent. He is killed by Arjuna while changing a chariot wheel on the grounds that, being a non-Kshatriya, he is not entitled to the courtesies of war. But Krishna, counsellor of Arjuna, knows that Karna is Kunti's son by the Sun-God and yet remains silent. Shyam Benegal's Kalyug was parametered by Mahabharata. And yet when it came to the Karna episode the film baulked the issue. In fact most of the New or Middle cinema has evaded taking a stand on the caste issue, apart from making polite noises about untouchability. In Govind Nihalani's Aakrosh, a Brahmin (Naseeruddin Shah) is the fighter for justice (a mokern Harishchandra), whereas Viswamitra is an Adivasi (Amrish Puri) who doesn't want to help his own people. In a very subtle fashion caste hierarchy is condoned, even approved of. Coming back to Harishchandra. He is put through terrible tests - the loss of wife Taramati into servitude, his own degeneration to the miserable occupation of a grave digger, the death of his son, and the injunction to execute his wife on a false murder charge. Finally the gods - the deus ex machina (god from the machine) intervene and restore the status quo. An interesting element is the way Phalke presents Siva. He looks like a man in a hurry, a pedestrian Christ, ready to set things right. There are certain elements in this film which have become a part of the cinematic repertoire of popular cinema. The first and foremost is the enactment of a perfect morality analogous to the performances of puja or acts of merit. This is the basic theme of almost every popular film - 'secular' or 'religious'. Secondly, generosity as a form of fulfilment of social obligations is considered as an integral part of the legitimation of high status. Claims to high status which are not accompanied by generosity are considered pretentious. Take any film of recent decades and you will find the upstart (uncle, servant, minister, manager) being mean in the patriarch's absence and humbled by the master on his return. Take Amitabh's role in Sharabi, of a generous alcoholic and reflect how many aeons away it is from Arthur, said to be its inspiration. The wife's selfless devotion to the husband comes down to as late as Avtaar and Amrit in the eighties. Harishchandra is the expression of the view that "altruism and consideration of the other members in the group are morally superior to a self-centred attitude". This may not be true of the daily events of Indian life but as a paradigm it has reverberated down the ages. A notable modern Harishchandra is Dharmendra in Satyakam, the honest Public Works engineer, who dies rather than accept bribes from contractors. The Harishchandra theme is also reflected in films of the seventies and eighties, like Deewar, Shakti, and Aakhri Raasta where brothers, fathers and sons fought each other in the name of 'duty', just as the Raja was prepared to execute his wife in the name of Dharma [legge, dovere religioso e morale]. Perfect morality requires extreme sacrifice and millions of cinematic wives have followed the example of the Raja's wife, Taramati. The need for some kind of symbolical sacrifice soon became a sine qua non of any respectable Hindi film. The most important element of Raja Harishchandra is the concept of deus ex machina - the appearance of the deities at the end to resolve the Raja's problems. In ancient Greek and Roman drama, a God is introduced into a play or plot to resolve a plot. This concept later became an unlikely or artificial device. Phalke must have been aware of this device in Victorian melodrama. But its use has a deeper meaning in the Indian context. Tapper (op. cit.) makes an important point when he says the plot of the drama illustrates the ideals of altruistic selflessness and truth carried to a logical extreme at which they produce benevolent intervention of the gods. Tapper is rather vague here. The real significance of the deus ex machina in Raja Harishchandra is expressed by Nirad C. Chowdhary in Hinduism. "In India, nature in all its aspects was in arms against man. Therefore, to win the battle against nature they had to seek the help ol the supernatural. A pattern of life had to be created in which the supernatural world would be able to reinforce human strength. In modern terms the collaboration between man and the supernatural spirits might be called religious feudalism, based on the principles of fealty, service and protection". Chowdhary's perceptive remark applies to the long history of Indian popular cinema, from Raja Harishchandra (1913) to Mard (1985) and Allah Rakha (1986). The concept of deus ex machina has not been critically studied. It is not merely a theatrical device as in the West; it is a clevice to "live by". Indian popular cinema is a religion-based strategy to "live by" in a hostile environment and an unjust society. In Mard and Allah Rakha the supernatural - Hindu and Muslim - intervenes. In Karma (1986) Siva is replaced by an apparently secular state, but one which is as stern to its enemies and as feudally patriarchal to its devotees as the gods. The variations by which the 1986 re-worked models of Raja Harishchandra catch the conscience of the new Kings - the masses - will be examined in later articles. Iqbal Masud Film citati nell'articolo (regista, anno, lingua): A cura di |