RAI TV

2015: ECO DELLA STORIA

'Eco della Storia'. Genocidi. Aired on history thematic channel 'Rai Storia' on Saturday January 24, 2015, and then as a nightly rerun on Rai Tre (Rai's third TV channel) on Wednesday February 26, 2015, at 1.15 a.m. (Clip ID: F664841).

This episode's section dedicated to the Holocaust also deals with the role played in it by Italy, and includes a video of Jewish testimonies recalling the expulsion from schools and the isolation inflicted on them by their classmates.

In the Tv studio, both the journalist host of the program, Gianni Riotta, and his guest, the historian Marcello Flores, underline the fact that the Italians "had stood by and watched" and, indeed, the fact that they "often took advantage of the situation", while the help given to the Jews only regarded "a few, minor instances". The proportions, compared to what was the dominant narrative up to the end of the Eighties, are now literally overturned.

(This program, however, had limited impact, given its scheduled transmission time)

2018: La grande Storia

'La grande storia'. 1938: 'Le leggi razziali'. By Ilaria Degano.

Aired on Tuesday, January 8, 2018 at 23.15 p.m. on RaiTre (Rai TV's third main channel).

Historical consultants: Anna Foa, Ernesto Galli Della Loggia.

The comments here shown made by the historian Ernesto Galli Della Loggia explicitly deny that Italians showed themselves to be "good people" towards the Jews at the time of the Racial Laws. Just before, the same point had also been made by the narrator's off-screen voice and by the victims themselves, Cesare Finzi and Ferruccio D'Angeli (through the same testimonies already given in 2008, see above).

The tone of the off-screen voice is one of peremptory condemnation, poles apart from the account heard for decades. ("Few and isolated are the voices that rise to condemn [the laws]. (...) But the reaction of the Italians is, in reality, mainly one of indifference and silence. In some isolated cases a possible reaction of protest is extinguished for fear of being accused of 'pietism'. (...) Many, on the other hand, are Italians who express full consent to the persecutory and racist policy of Fascism. And even more are those who turn away and prefer not to see ").

2018: Che tempo che fa

'Che tempo che fa'. Broadcast on September 23, 2018 at 8.35 p.m. on RaiUno.

(Clip ID: X900058114). An interview with Liliana Segre.

The very first episode of the new season of Fazio's hugely popular talk show features a long 25-minute interview with Senator Liliana Segre, a Shoah survivor. In this excerpt her testimony on the Racial Laws is particularly effectively in focusing on the danger of indifference, the capital sin she ascribes to the Italians of the time and the danger against which she warns today's younger generations. Segre, therefore, gives an anything but comforting account of the behavior of the Italians of the time. Still, she is invited back to the program, one of Rai's most popular, to talk about such issues no less than 5 times between 2018 and the beginning of 2020. This can be seen as another sign of a shift in perspective with regards to these events.

2018: TV Storia

TV Storia. 1938: L'Italia e le leggi razziali. Broadcast on October 26, 2018 at 9.40 p. m., on Rai Storia (No Clip ID).

IOn the 80th anniversary of the Racial Laws, Rai Storia (Rai's history thematic channel) devotes to the subject an episode of its in-depth program “TV Storia". One of the three pivotal questions posed by the host Massimo Bernardini is: «How did post-war Italy deal with this burdensome legacy?». The very fact of posing this question and focusing the episode on it signals a more mature awareness of the issue.

Riccardo Di Segni, head rabbi of the Jewish community of Rome, Emilio Gentile e Alessandra Tarquini, two prominent historians on Fascism were the guests for the evening.

Rabbi Riccardo Di Segni: postwar and denials

In this first excerpt, Rabbi Di Segni recalls the salient points of the collective denial of the racial persecutions that characterized the post-war period, even by the Jews themselves.

Alessandra Tarquini: the Italians before the racial laws

Alessandra Tarquini states here that at the time "no one protests" against the racial laws (starting with the intellectuals), because "after all, Italians are not particularly shocked by this anti-Semitic legislation". Emilio Gentile then summarizes the reasons for this widespread attitude.

Emilio Gentile: that assessment by De Felice

In the course of the episode, Gentile is shown the above-mentioned 1965 video interview drawn from 'La lotta per la libertà' (watch the extract above), in which Renzo De Felice talked of "the moral reaction of the country" that would have "immediately" followed the Racial Laws, causing "the first major rift between fascism and the Italian people”. Asked for a comment on this, Gentile has to correct his own old professor, while defending and contextualizing him.

Emilio Gentile: the risks of a collective self-absolution

The revision of De Felice’s position is reiterated here by Gentile, who also adds a caveat on the fact that democracies are susceptible to racism too, especially when they lull themselves into collective self-absolutions. So, with De Felice’s comments of 1965 corrected by his pupil Gentile in 2018, that is, with the "first" TV historical reading of the Racial Laws explicitly surpassed by the most recent one, the television story of this theme somehow closes a loop.

2019: Figli del destino

Di Francesco Miccichè e Marco Spagnoli. Broadcast on January 23, 2019 on RaiUno at 9.25 p.m. (Clip ID: X000037650).

Approaching Holocaust Remembrance Day of that year, RaiUno experiments a different way of dealing with the issue: the docudrama (referred to as 'docu-fiction' in Italy), albeit with not very rewarding ratings (fewer than 3 million viewers, 12.4% share). Making use of actors as well as comments by historians, of period films and fictional re-enactments, Figli del destino (Sons of destiny') narrates the stories of four Italian Jews under racial persecution, following their own personal testimonies, gathered in interviews.

"I didn't make these laws myself!"

The personal stories presented in this 'docu-ficion' are those of Liliana Segre in Milan, of Tullio Foà in Naples, of Lia Levi in Rome, of Guido Cava in Pisa. Three out of four of them concerned Jews saved by Italians (respectively by a police commissioner, by a convent of nuns and by a fascist doctor). This proportion has little correspondence to historical reality. However, most of the program is dedicated to the fourth story, the one of Segre's family, where there are no saviors but indifferent schoolmates and teachers (such as in this extract) and...

Michele Sarfatti: reactions and tacit consent

...Besides, the docudrama also includes a brief speech given by the historian Michele Sarfatti, in which he emphasizes the substantial absence of protests from Italian society, the King and the Vatican.

(Actually, the pope Pio XI had condemned the racial laws, enough to irritate Mussolini. But he had died soon after that, on Feb. 10 1939, and his successor, Pio XII, had chosen the line of silence).

Also on this last point a change of interpretation can be observed, in the sense of a stronger emphasis (in TV programs and even more in the historiography) on the insufficient character of the Vatican reactions (if without denying the aid given by religious persons and Church organisations).

2020: La guerra è finita

Di Michele Soavi. Broadcast on January 13, 20, 27 and February 3, 2020, on Monday during prime time on RaiUno (ID Teca: X000052573; X000052662; X000053605).

This miniseries is inspired by the true story of the 800 Jewish orphans who survived the Shoah and who were welcomed to an estate in Selvino, a small town in the Bergamo area, as of 1945. Many of these subsequently left for Palestine..

La guerra è finita (“The War is Over”) received excellent feedback from both critics and the general public, with a constant viewing audience of over 4 million per episode, resulting the most-viewed program on all the four evenings it was shown. The series is a work of fine workmanship, containing different meanings and levels of fruition. It features "good" Italian characters, but also "bad ones". It confirms that an evolution is underway also in the genre of the popular storytelling.

"They don't have just you"

This scene, taken from the first episode, portrayed the traditional story (one that was also true, let's restate it), that of the help given by some ordinary people to the Jews, for humane reasons.

"These are things that must be kept silent"

The second episode of the miniseries stages a conversation between Ben, the former headmaster and Jewish fighter, and Giulia, the young Italian psychopedagogist, who together set up a recovery community at the end of the war for child Holocaust survivors. The dialogue show the victims’ strong drive to remove what had happened to them and, at the same time, the need to counter it, also in order to spread awareness about said events.

"There were black shirts"

This scene is drawn from the fourth and final episode of the miniseries. Here, Nicole, one of the Jewish teenagers hosted in Selvino, painfully tells Giulia about the harsh racial persecutions inflicted on her and fellow Jews by the Italian fellow-citizens, years before the Nazi occupation. In listening to the stories, Giulia herself appears bewildered and seems to become truly aware of what had occurred for the first time. The portrayal of this character is particularly significant because it embodies the country's need to deal with its responsibilities. In fact, Giulia, as the well-off daughter of a father who traded arms with the Nazis, blames herself for not having protested against him and, finally distancing herself from him, seeks a moral and civil "redemption" in this commitment in aid of the survivors. This kind of scene would hardly have been seen during prime time on RaiUno in previous decades. The miniseries ends emblematically with the Selvino estate becoming a seat for the institutional referendum of 1946. The metaphor is clear. Tying up the loose ends with the national past implies acknowledging it, and if possible trying to redeem it, not denying or sweetening it. Only then can a new leaf be turned.

Historiography and Memorials

Storia della Shoah in Italia

2010: The monumental two-volume collective work Storia della Shoah in Italia (“History of the Shoah in Italy”) is released. Published by Utet and edited by historians Marcello Flores, Simon Levis Sullam, Marie-Anne Matard-Bonucci and Enzo Traverso, the volumes count 50 chapters (click HERE for the index) that were written by as many Italian and international historians, each on a different aspect of the phenomenon, from its historical premises to its memory.

Gli ebrei sotto la persecuzione in Italia

2011: hrough hitherto neglected personal documents such as diaries and letters from Jewish citizens, this volume ('The Jews under the persecution in Italy') shows the individual impacts of racial laws.

We read from the introduction: "The truth is that Italy and the Italians independently embarked on the persecution of the Jews and carried it out systematically, determinedly and effectively" (p. XIII)

Author:

Mario Avagliano

Author:

Marco Palmieri

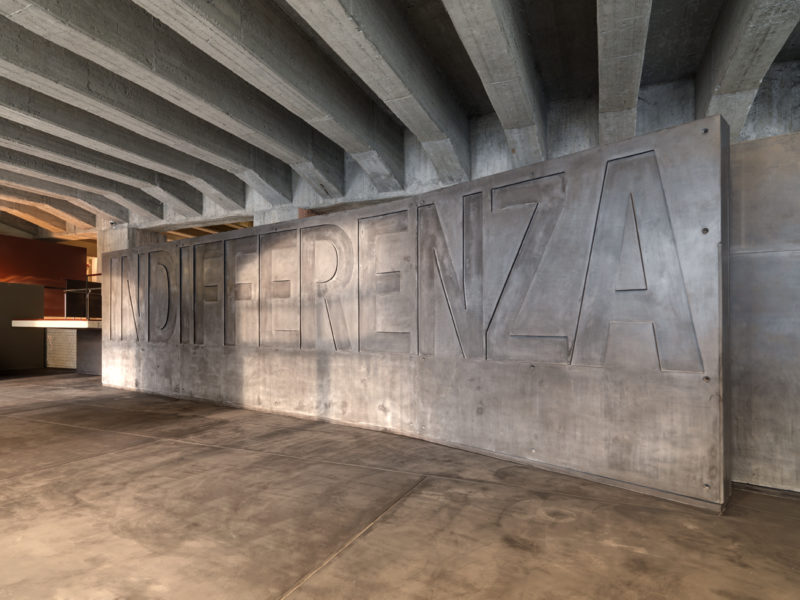

Di pura razza italiana

2013: The book Di pura razza italiana. L’Italia ‘ariana’ di fronte alle leggi razziali (“Of Pure Italian Race: ‘Aryan’ Italy and the Racial Laws”) by Mario Avigliano and Marco Palmieri is released. This is a continuation of the two journalists-historians’ previous volume but focusing this time on the non-Jewish Italians and using other archival sources, such as information from the regime's trustees, reports from the Minculpop, etc. The authors conclude their analysis by stating that “the prevailing attitude (…) was undoubtedly indifference. (...) The ‘See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil' practiced by the majority of Italians (...) helped to achieve the goal of persecution, namely, isolation, separation and the exclusion of Jews from the rest of society "(pp. 17-18).

Author:

Mario Avagliano

Author:

Marco Palmieri

Il cattivo tedesco e il bravo italiano

2013: The historian Filippo Focardi publishes Il cattivo tedesco e il bravo italiano (“The Bad German and the Good Italian”). In this study he shows the ways and reasons (also involving international politics) for which in the post-war period all blame for the crimes of the Second World War was systematically placed on the Germans, while at the same time creating an opposing image of the "good Italian", meek and supportive.

Surely, Focardi points out, aid given to the Jews existed. He notes that "behind the stereotype there was a substantial core of truth. And, yet, the stereotype served to cover the downside that was no less relevant but much more regrettable, namely, the adherence of a number Italians to the 'Imperialist War' of Fascism, the numerous war crimes committed in the occupied territories (…); the involvement in the Germanic persecution of the Jews (...) a number of 'Italian bad people' ready to take advantage of the persecuted (...) "(p. xiii-xiv).

Author:

Filippo Focardi

The Holocaust in Italian culture (1944-2010) - Scolpitelo nei cuori

2013:Meanwhile, studies on the memory of the Shoah have also begun, such as Guri Schwarz’s Ritrovare se stessi. Gli ebrei nell’Italia post-fascista (“Finding yourself again. Jews in post-Fascist Italy”, 2004) and two studies undertaken abroad, Emiliano Perra’s Conflicts of Memory (2010) and Robert Gordon’s The Holocaust in Italian Culture (1944-2010) (2012, translated into Italian in 2013 as “Scolpitelo nei cuori”).

Author:

Robert S. C. Gordon

I carnefici italiani

2015: In his book I carnefici italiani ('The Italian perpetrators'), the historian Simon Levis Sullam documents the many cases (hitherto not investigated) of informers, spies, extermination propagandists and so on. We read here that "this book claims that, in 1943-1945, the Italians who declared the Jews ‘foreigners’ and ‘enemies’, identified them on a racial basis (...), tracked them down house by house, arrested them (...) handed them over to the Germans, they were responsible for a genocide." (p.11). We also read that “too often only the saviors have been spoken of” (p.13) and that "even though seventy years have passed since those events, there has not yet been an explicit assumption of responsibility and gestures of firm self-criticism and reparation by the Italian government, whose police forces and administrations directly contributed to the genocide of the Jews "(p.119)

Author:

Simon Levis Sullam

Salvarsi. Gli ebrei d'Italia sfuggiti alla Shoah. 1943-1945

2017: Liliana Picciotto releases the book Salvarsi. Gli ebrei d'Italia sfuggiti alla Shoah 1943-1945 ('Saving oneself. The Italian Jews that escaped the Shoah 1943-1945'), flipside and integration of Liliana Picciotto's previous study ('Il libro della memoria'). Basing on 9 years of research, the historian investigates the fate not of those who lost their lives in the persecutions, but of those that were able to save themselves, i.e. the 81% of Italian Jews. And even reconstructing in details the circumstances and reasons of the many aid received by the Jews, Picciotto eventually attributes their high rate of survival to "a phenomenon of collective resilience" of the Italian Jews, rather than to an elusive "average good Italian" (p.506).

Author:

Liliana Picciotto

Sotto gli occhi di tutti. La società italiana e le persecuzioni contro gli ebrei

2018: On the occasion of the 80th anniversary, further studies are published, all ascribable to this trend of interpretation, such as V. Galimi, Sotto gli occhi di tutti. La società italiana e le persecuzioni contro gli ebrei ('Under the eyes of all. Italian society and the persecutions against Jews'); A. Capristo-G.Fabre, Il registro ('The register'); F. Isman, 1938, l’Italia razzista ('1938, racist Italy'); C.Vercelli, Francamente razzisti ('Frankly racists').

Author:

Valeria Galimi

Culture and Politics

2013: Attending the inauguration of the Shoah Memorial in Milan on the occasion of the Day of Remembrance, the center-right leader Silvio Berlusconi talks once again of the Racial Laws as a result of a German imposition on Italy (Here).

2018: Liliana Segre, a survivor of Auschwitz and later committed for decades to bearing witness of the memory of what happened, is appointed Senator for Life by the President of the Republic.

2019: In Rome, three streets that were still dedicated to the scientists who signed the 'Manifesto della razza' (Manifesto of the Race) are re-named after three scientists expelled from the University by the Fascist regime. These were Nella Mortara, Enrica Calabresi, expelled as Jews, and Mario Carrara, expelled because he refused to swear allegiance to the regime. The new road sign plaques are immediately vandalized by unknown persons.

2019:The Italian Parliament votes the establishment of the “Segre Parliamentary Commission" (so called after the name of its first promoter) "to combat the phenomena of intolerance, racism, anti-Semitism and instigation to hatred and violence ". In a controversial move, the center-right senators abstains during the vote. A week later, 89-year-old Senator Segre is placed under guard due to the approximately 200 daily threats she has been receiving.

(The photo shows Sen.Segre in Milan escorted by Carabinieri)

2020: On Holocaust Remembrance Day, the President of the Republic Mattarella states that "the persecution of Italian Jewish citizens in Italy, under the Fascist regime was not, as some still like to think, watered-down. It was fierce and merciless. And half of the Italian Jews, deported to the extermination camps, were captured and sent for deportation by the Fascists without the direct intervention or specific request of the German soldiers."