Palladium against ovarian cancer: Ca’ Foscari patents head for the market

Research, particularly in the medical and pharmaceutical sectors, can significantly affect people’s lives when a company supports its development and helps bring it to market. A recent example is the transfer of two patents from Ca’ Foscari University’s Department of Molecular Sciences and Nanosystems, which relate to a new generation of anti-tumour agents.

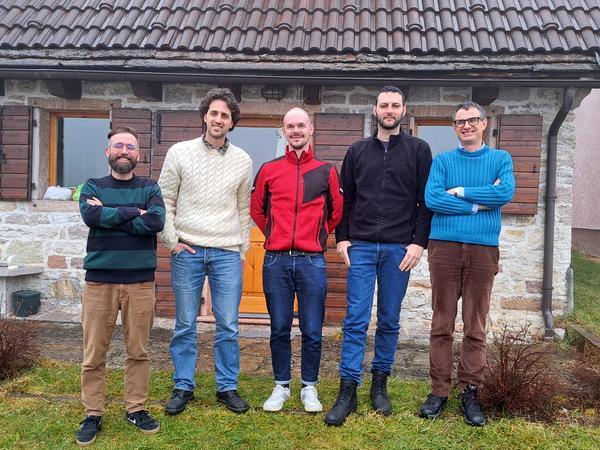

Flavio Rizzolio, Professor of Molecular Biology, and Fabiano Visentin, Professor of General and Inorganic Chemistry, have been studying palladium compounds for years with the aim of attacking cancer cells. The patented inventions include two categories of compounds: the first patent, granted in 2021, concerns dimeric Palladium(I) complexes; the second, granted in 2023, concerns vinyl and butadienyl Palladium(II) compounds.

The pharmaceutical company Galenica Senese, which mainly specialises in medical devices and infusion and injectable drugs, has recently acquired the industrial property rights to both inventions — patented by Rizzolio and Visentin together with Dario Alessi, Thomas Scattolin and Enrica Bortolamiol — and has been collaborating since 2023 with Ca’ Foscari’s research groups on a project funded by the Italian Ministry of Enterprises and Made in Italy, aimed at introducing these compounds to the market as formulations for the treatment of solid tumours.

“This line of research on the preparation of metal-based drugs began in 2016, when Flavio Rizzolio joined the Department of Molecular Sciences and Nanosystems from the CRO National Cancer Institute (Centro di Riferimento Oncologico) in Aviano,” explains Fabiano Visentin. “We combined two different areas of expertise: on one hand, Flavio’s solid background in oncology and genetics; on the other, our long-standing experience in preparing organometallic compounds — mainly, though not exclusively, palladium-based ones. Palladium is a rather rare transition metal with numerous industrial applications, especially as a catalyst in various processes. We then questioned why palladium was so seldom used in pharmacology and medicine, despite its close relative, platinum, forming the basis of cisplatin — a compound that, together with its second- and third-generation derivatives, is utilised in about 50% of treatment protocols for various cancers. So we started synthesising new palladium compounds and focused on a particularly difficult type of cancer — ovarian cancer. It is almost asymptomatic, and when the first signs appear, it is often too late. Patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy respond very well initially, but in cases of recurrence — unfortunately frequent with this disease — the drug becomes virtually ineffective. We wanted to find something useful for this second phase of therapy, when the first-line drugs are no longer effective.”

What is the structure of these compounds?

“These compounds have a metallic core, that can be intrinsically toxic to the tumour cell and is surrounded by an organic fragment that can also inhibit cancer proliferation,” Visentin continues. “This allows for a combined action: the drug can potentially target different cellular mechanisms simultaneously, causing multiple types of damage to the tumour cell and bypassing its defence systems. Since we began our collaboration, we’ve synthesised and tested over 200 compounds, with rigorous screening carried out by Flavio’s research team to assess their antitumour activity, after which my group made structural modifications to maximise performance.”

How do you test the compounds?

The tests we commonly conduct are:

- In vitro tests on both cancerous and healthy cell cultures, to determine whether the drug acts selectively on tumour cells or also affects healthy ones, even slightly. This is essential to minimise side effects, which are common in many chemotherapy treatments.

- After this first feedback, Flavio’s team performs tests on tumour organoids, three-dimensional cell cultures that more closely resemble real tumour tissue. These are obtained from actual patients, using tissue fragments collected at the CRO in Aviano in collaboration with Professor Vincenzo Canzonieri, Head of the Department of Pathological Anatomy. This allows us to obtain more reliable results.

- In the most promising cases, we move on to in vivo testing, including assessments of the drug’s systemic toxicity.

The patented compounds

The patents cover two categories of compounds that have shown the most promising results, though they are not the only ones. They present some significant advantages:

- They are selective, mainly targeting tumour cells and having less effect on healthy ones.

- They work effectively on platinum-resistant cell cultures. As mentioned, carboplatin is the first-line treatment for ovarian cancer, and there is now an urgent demand for drugs that can act on relapsing patients.

- They show relatively low systemic toxicity.

All the conditions, therefore, appear to be in place for the development of a new drug.

What are the next steps? When could these become medicines in use?

“We are currently studying ways to ensure that the drugs reach the right place — the tumour site — without harming the rest of the body,” says Visentin. “We are collaborating with Galenica Senese to encapsulate these drugs in liposomal structures, which would extend their persistence in the body and deliver the drug directly to the tumour.”

“Transforming a compound into an actual medicine is a complex process,” adds Rizzolio. “Drug development follows specific trends. For instance, the drugs we see on the market today were typically developed 10 to 15 years ago in pharmaceutical laboratories. Nowadays, we are seeing a shift towards biological drugs, such as antibodies, and away from traditional chemotherapy. Our compounds, however, are chemotherapeutic agents with an important advantage: high selectivity. They could therefore complement standard ovarian cancer therapies. But for them to reach the market, pharmaceutical companies need to show interest, to take these laboratory-developed molecules, re-synthesise them according to current regulations, and begin patient trials. This requires multi-million-euro investments, so much depends on the companies.”

How is your research progressing in the meantime?

“One of our medium-term goals is to create a database of metal-based drugs that could continue to support ovarian cancer research,” says Visentin.

“Fabiano’s team is also exploring ways to move closer to the world of antibodies,” concludes Rizzolio. “We are experimenting with linking the drug to a monoclonal antibody, a biological entity capable of actively recognising tumour tissue and delivering the drug precisely to the site. Antibodies themselves often have therapeutic effects, so the drug’s action would combine with that of the monoclonal antibody. It is certainly a complex path, but one worth pursuing.”

Both the patenting process and the management of relations with the company — from transferring patents to sustaining collaboration — have been supported by PInK – Promoting Innovation and Knowledge, Ca’ Foscari’s knowledge transfer office, which fosters a culture of industrial property to encourage investment in research and development.