350 Million Voices Sharing One Root: A Journey into Bantu Languages with Prof. Félix Tembe

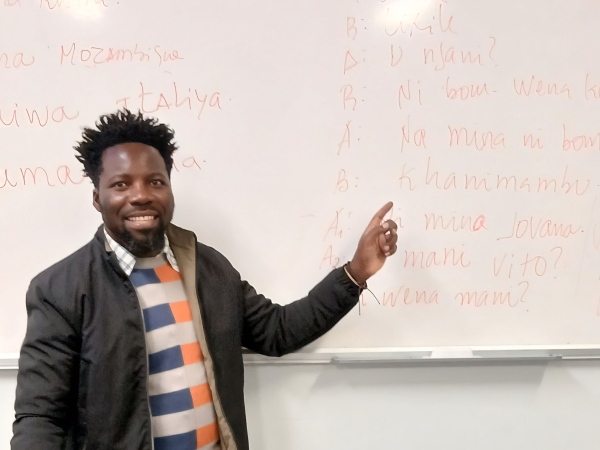

In the lecture halls of Ca’ Foscari, people are talking about kiSwahili, xiChangana and isiZulu: sounds and words that tell stories, identities and world views. Guiding this journey is Professor Félix Filimone Tembe, a lecturer in Bantu Linguistics at the Universidade Eduardo Mondlane in Maputo, Mozambique, who over the past few weeks has held at Ca’ Foscari the first introductory course dedicated to the great family of Bantu languages.

The series of lectures, which concluded on 14 November, stems from the desire to strengthen the presence of African Studies at the University by introducing new linguistic training pathways dedicated to the continent, open to all Ca’ Foscari students. It is the first step in a broader project, which will continue next year with an introduction to Swahili.

Delivered as part of an Erasmus exchange programme, the course was made possible thanks to the collaboration between the Middle East and Africa curriculum of the Bachelor’s Degree Programme in Languages, Cultures and Societies of Asia and North Africa (Department of Asian and North African Studies) and the Master’s Degree Programme in Cultural Anthropology, Ethnology, Ethnolinguistics (Department of Humanities), with the contribution of Prof. Francesco Vacchiano and Prof. Barbara De Poli.

We spoke with Professor Tembe to find out what makes Bantu languages unique, how they spread across much of Africa and why they remained to this day one of the deepest expressions of the identity and collective memory of the peoples who speak them.

What are Bantu languages and how did they develop?

The Bantu languages form a large linguistic family comprising more than 650 languages and over 350 million speakers, mostly concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa.

Sharing a common origin, Bantu languages display structural similarities, especially at the morphological level: they are strongly agglutinative languages, with precise and parametric grammatical structures.

The Bantu group, which stretches from the Cameroonian highlands (the Shaba plateau) to South Africa, represents the most significant branch of the Niger-Congo family. Among the most widespread languages are Kiswahili (an African lingua franca), Kikongo, isiZulu, iLingala, xiShona and xiTsonga (which includes three mutually intelligible varieties: xiChangana, xiZronga and ciTshwa).

According to linguistic literature, Proto-Bantu – the mother language from which all Bantu languages derive – developed over 3,000 years ago in the area between south-eastern Nigeria and Cameroon.

These languages are spoken by millions of people across Africa. What enabled them to spread so widely, and what makes them different from one another?

The major expansion of Bantu peoples is linked to several factors: technological development (above all metallurgy, which transformed agriculture, hunting and defence), mobility and commercial exchange.

Starting from the Cameroonian highlands, Bantu groups followed rivers, savannahs and valleys in search of lands suitable for agriculture and trade. Environmental pressures, such as the difficulty of surviving in the vast tropical forests, further encouraged these migrations.

An emblematic example of this mobility is kiSwahili, now spoken in many East African countries: it emerged from contact between Bantu groups and Arab and Persian merchants along the coast, incorporating numerous loanwords from Arabic.

Bantu expansion was also facilitated by mixed marriages, cultural assimilation, and the subjugation of local populations such as the Pygmy, Khoi, and San peoples. Geographical distances and linguistic contact created significant diversity among Bantu languages.

On the one hand, contact with local languages altered phonetics, morphology and vocabulary; on the other, territorial distance led to the formation of regional variants. Despite this, Bantu languages retain the fundamental features of Proto-Bantu, such as noun classes. The linguist Wilhelm Bleek (1827–1875) coined the term Bantu through comparative studies, recognising these affinities. Later, Malcolm Guthrie (1948-1971) classified Bantu languages into geographical (not genealogical) zones, distinguishing, for example, zone S50–Tshwa–Ronga/Tsonga, which includes xiChangana, xiZronga and xiTshwa – all mutually intelligible and differing only slightly at phonetic level.

How do these languages help shape people’s sense of identity and community in Africa?

After breath, language is the most intimate and vital element of human existence. Through language we express who we are, what we feel and what we think.

Bantu languages, more than mere tools of communication, are profound symbols of identity: vehicles of social cohesion, belonging, collective memory and ancestral heritage. Every Bantu language is both the medium and the expression of its speakers' culture. It is the living link between generations and their history: orality, spirituality, the relationship with the land, and the collective sense of responsibility, rights and duties. Through folklore, songs, stories and personal names (place names and anthroponyms), these languages transmit knowledge and world views.

During the colonial period, Bantu languages were often repressed or silenced, yet they continued to survive as instruments of resistance: through songs, metaphors and coded expressions that preserved cohesion among oppressed communities.

With African independence, many Bantu languages were reclaimed as symbols of freedom and national identity. In South Africa, for instance, all Bantu languages are official alongside English, Afrikaans and Sign Language. Kiswahili is an official language in several African countries and also one of the African Union’s official languages. In Mozambique, nineteen Bantu languages are currently used in primary education through the bilingual teaching system (Decree-Law 18/2018).

Mother-tongue learning enables children to develop a strong sense of identity and patriotism, as well as greater cultural understanding and better academic performance. Yet, like all living languages, Bantu languages evolve: modern life and technology have given rise to urban varieties that incorporate lexical and phonetic elements from dominant European languages.

What do you hope students will take away from this introductory course?

In this introductory course on Bantu languages, I hope students will gain a basic understanding of their phonetic, grammatical, and cultural features; recognise the connection between language, culture, thought, and identity; and perhaps develop an interest in the socio-anthropological aspects that accompany Bantu languages and their speakers.

Could you give us an example of a peculiar or unique feature of Bantu languages?

One of the most fascinating features of Bantu languages is undoubtedly ideophones – linguistic elements that create a direct link between sound and perception.

They are often described as “image-words” because they evoke sensory experiences: sounds, colours, movements, emotions, textures or states.

For example, in xiChangana:

dúum! – indicates a state of pensiveness, as in Mujondzisi ayo dúum (“the teacher is deep in thought”), whether seated or leaning. In this case, the noun does not distinguish gender: mujondzisi may refer to either a man or a woman.

Báááá! – conveys the idea of “clean/white/bright”.

Tile riyo baaa hi tinyeleti – literally “The sky is white with stars”, meaning “The sky is clear, full of stars”.

These examples show how, in Bantu languages, sound and meaning are closely intertwined, and how language reflects the sensitivity and world view of its speakers.