Neither

Pakeezah with its cloistered claustrophobia nor

Santoshi Ma with its evocation of a chancy universe could satisfy the mood of the seventies. The door to current history was kicked open by the New Hero. The anti-hero of the seventies. It is generally identified with Amitabh Bachchan, but there were other strong contenders to the throne - Dharmendra, Vinod Khanna, etc. What is relevant is the persona of the new hero, not the specific person. In view of the large number of films involved I shall isolate some of the characteristics of the new hero and illustrate them from the films.

Actually there are two variants of the new hero - the action-oriented hero and the more contemplative, introverted noble hero. Let's analyse some of the elements of the action-oriented hero.

|

Ānand (1970) |

The Hero as Saviour: It is this element which sets the new hero apart from cinema's earlier heroes who were victims, sufferers, alcoholics, ineffective angels, poets, idealistic teachers, etc. Of course,

Mother India and

Ganga Jumna are there as source works of new popular cinema - as much as Huckleberry Finn is for the American novel. But the hero as Saviour was not typical of the pre-seventies cinema. The seventies hero has some special peculiarities. Let us take

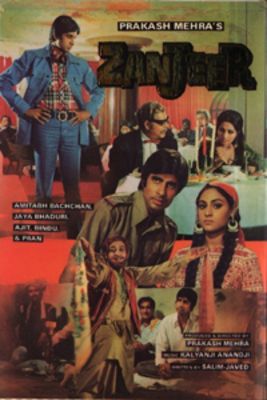

Zanjeer for instance and then see the types created by it. The aggressively honest Inspector (Amitabh); the seemingly outsider female mate, knife sharpener here (Jaya Bachchan), who is quickly reduced to domesticity, the enemy Pathan, who is quickly reduced to male bonded comrade; the System (mafia drug peddlars, ineffective police officers) which the hero fights. All the stereotypes of the seventies and eighties are here.

A saviour is also a self-sacrificer. The Zanjeer (Chain) of the title is the chain of domesticity. The hero has to choose between a domestic life with his beloved or the deadly fight in the world outside. What is new about the new hero is his quiet, unostentatious morality. But the form of the masala (curry) film forces glamour on the hero. The quiet periods of reflection and analysis vanish and the hero is lost in the giant battles which have become now a permanent part of cinema. From this point on, the hero becomes a plastic figure. He cannot wait to take up causes. He may do it reluctantly as in Sholay or zestfully as in Muqaddar Ka Sikander. But he does it with deliberation, gusto and bravura and goes to his death in style. Sacrifice has become a knee jerk reaction. Not a human act with its mix of trepidation and courage.

|

Muqaddar kā Sikandar (1978) |

The Hero as Upstart/Climber: Keeping in mind the large lumpen or semi-lumpen elements in the urban slum market, the hero gradually descended from the respectable middle class status of Zanjeer to become a child of the slums. See

Muqaddar Ka Sikander,

Naseeb,

Amar Akbar Anthony, etc. In some instances, the hero is unmasked as of middle class or noble descent. The important point is that the hero makes it to the middle or upper class in many cases. Early in

Muqaddar Ka Sikander a Dervish exhorts young Amitabh,

Zinda hai woh jo maut se takrate hain. Tu muqaddar ka Sikander ban ja. [Vivo è colui che si lancia contro la morte. Tu diventa l'Alessandro del tuo destino]. This mystical exhortation is translated into bourgeois practicality as Sikander rises in business by informing on smugglers. Moral: in a capitalist economy the hero can rise honestly if not interfered with by the corrupt police or the mafia. This implicit assumption runs through the most radical masala film and makes it a part of the very system it apparently seeks to condemn.

The petite bourgeois vision informs many of seventies Hero films. In Naseeb Amitabh slaves to keep his brother at a public school; in Sholay he is attracted by aloof cultured Jaya, playing a young widow while tongawali Hema Malini is allotted to the more peasant-like Dharmendra. In later films like Sharabi, the hero behaves towards Jaya Prada as a lord to a maid. In Lawaris the hero fights to claim his respectable position which is denied to him because of his unrecognised descent. In this sense the seventies hero is a sheep in wolf's clothing. Perhaps it truly reflects the secret - or not so secret - wishes of the petite bourgeoisie and the lumpens among the audiences.

|

Zanjīr (1973) |

The Hero as Macho Elitist Egoist: The populist image of the hero is really a facade. He is not a Man of the People. His machismo is of course his obvious quality but this is not the understated masculinity of the Western. It is a bawling, bellowing, braying, calling-attention-to-self machismo. One part of this machismo is male bonding -

Zanjeer to

Amar Akbar Anthony and a hundred other films. It is difficult to think of this bonded group as a body of equals. Gradually one hero (

Amitabh) outstrips all the rest. This is the basic falsity of the popular cinema.

It takes an objective reality - corrupt system and exploiters - and twists it in such a way that the cinematic image actually justifies the existing reality. As the oligarchic group turns into a single hero despotism, megalomania supersedes heroism - see the eighties films Coolie and Mard.

The hero is in fact a veil for an unappetising mix of elitism and egoism. If you watch the films of the seventies closely you'll find an implicit contempt for the ordinary decency of ordinary people. A study of the wardrobe of the hero in the seventies and eighties would be illuminating. The dresses are not merely flashy. They convey oneupmanship, even domination. Gradually the black boots of the hero come to dominate the close ups. A fascist symbol if ever there was one.

Another consequence of the hero image is the contemptous attitude towards women. The tongawali Hema Malini image of Sholay is phony and its phoniness is exploded in the sado-masochistic last scene of the film. But for its prudery it could be well out of Sade's books. The men of Sholay may be stagey, they are not phony.

|

Shole (1975) |

The Hero as Clown: One unmistakable mark of the seventies ethos is that the hero does not take himself too seriously. There is a calculaled self-parody. Amitabh excelled in this. It is perhaps his prime contribution to cinema. See

Amar Akbar Anthony to

Mard. But one point is often missed by critics. The clowning does not diminish the hero. It enhances him. The clowning says: "See, I am as human as you. Yet I am superior to you." The clowning is generally used to humiliate the enemy.

|

Muqaddar kā Sikandar (1978) |

The Hero as the Incurably Wounded: There is one aspect of both the activist and the pacifist hero of the seventies which is fascinating,but which I set down with some hesitation because of its ambiguity. Edmond Wilson in his The Wound and Bow speaks of the Greek mythical master archer (similar to

Arjuna) Philocteses, whose arrow never missed its mark but who suffered from a near incurable wound. This caused his fellow Greeks to desert him. In the Sophocles play, the injury and the grievance confer on Philocteses a dignity and strength. Superior strength or talent is inseparable from some disability. The hero who has an incurable wound has a perverse kind of nobility. Misfortune and sufferings enable a man to perfect himself.

The idea is not foreign to the Indian tradition. It is echoed in Guru Dutt's self image in Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool. But it is strange to find it surfacing in the bogus macho world of the seventies hero. But it does, and this is what gives some complexity and dignity to the hero. Its reverberation is strongest in Zanjeer and Muqaddar Ka Sikander. The hero in both the films is, at some level, profoundly unhappy. Even in the trashy ambience of these films, he conveys a sense of the basic tragedy of life itself - at least as Amitabh plays it. The vulnerability of domestic life or the impossible love for Raakhee are no doubt the ostensible causes for unhappiness. But the performances display a deeper psychological disturbance explored further in the next section.

The Introvert Noble Hero: Hrishikesh Mukherjee's three films, Anand, Namak Haram and Bemisal show the tragic side of the hero in a more explicit fashion than the action films. (...) There is an interesting line of development here. In Anand, the hero's agony is the incurable condition of humanity itself. There are echoes of the famous awakening of Prince Siddhartha to human misery. In Namak Haram the hero gets into the crossfire of class war. He wants to reach across the class barriers to his old friend - but in this war no prisoners are taken. Bemisal is the most interesting of the three. Superficially, the theme here too is male bonding; the women are marginal. But if you put that issue out of the way, certain other resonances emerge. The hero is maimed for life by his early poverty. Something of the early deprivation and injustice has burned an incurable wound, a hatred into his psyche. Even when he befriends a rich doctor,these hurts persist. He loses the girl (Raakhee) to him. But an undertone of sexual play persists even after marriage. He pursues an early femme fatale of his elder brother (whose life she had ruined) with a vengeful ferocity and vulgarity unmatched in the Amitabh oeuvre. Amitabh nobly saves his doctor friend by blackmailing a nurse and falsely accepting the blame.

I think in Bemisal most of the ingredients of the seventies hero are trapped in a highly visible fashion - upstart, clown, incurably wounded victim, savagely resentful and revengeful despot, death wish obsessed man. His nobility conceals all this under an acceptable mask. Nevertheless the tragedy is real. A flawed, bogus but tragic hero for a flawed, bogus and tragic age.

Note

Masālā (spezie) era il termine più usato per indicare il cinema popolare prima dell'ormai vincente Bollywood.

Film citati nell'articolo (regista, anno, lingua):

Amar Akbar Anthony (Manmohan Desāī, 1977, hindi)

Anand (Ānand, Rishikesh Mukharjī, 1970, hindi)

Bemisal (Bemisāl, Senza pari, Rishikesh Mukharjī, 1982, hindi)

Coolie (Qulī, Il facchino, Manmohan Desāī/Prayāg Rāj, 1983, hindi)

Ganga Jumna (Gangā Jamnā, Gangā e Jamnā, Nitin Bos, 1961, hindi)

Kaagaz Ke Phool (Kāghaz ke phūl, Fiori di carta, Guru Datt, 1959, hindi)

Lawaris (Lāvāris, Senza Famiglia, Prakāsh Mehrā, 1981, hindi)

Mard (Uomo, Manmohan Desāī, 1985, hindi)

Mother India (Mahbūb, 1957, hindi)

Muqaddar Ka Sikander (Muqaddar kā Sikandar, L'Alessandro del proprio destino, Prakāsh Mehrā, 1978, hindi)

Namak Haram (Namak harām, Il traditore, Rishikesh Mukharjī, 1973, hindi)

Naseeb (Nasīb, Destino, Manmohan Desāī, 1981, hindi

Pakeezah (Pākīzā, Cuore puro, Kamāl Amrohī, 1971, urdu)

Pyaasa (Pyāsā, L'assetato, Guru Datt, 1957, hindi)

Santoshi Ma (Jay Santoshī Mān, Viva la Madre Santoshī, Vijay Sharmā, 1975, hindi)

Sharabi (Sharābī, L'ubriacone, Prakāsh Mehrā, 1984,hindi)

Sholay (Shole, Fiamme, Ramesh Sippī, 1975, hindi)

Zanjeer (Zanjīr, La catena, Prakāsh Mehrā, 1973, hindi)